Nobelles of Medicine – Celebrating Exceptional Women Who Won the Nobel Prize in Medicine & Physiology

Back to Posts

Celebrating Exceptional Women Who Won the Nobel Prize in Medicine & Physiology

Written by: Alison Müller

In celebration of Women’s History Month, we are shining the spotlight some phenomenal women in the medical science field that have been awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine & Physiology.

Even though this prize has been awarded 115 times to 229 people since 1910, only 13 winners have been women winning shared prizes. The women highlighted today are truly international as they hail from the Czech Republic, Australia, the US, and China. Their work ranges from better understanding genetic elements, uncovering important steps in metabolism, to fighting malaria.

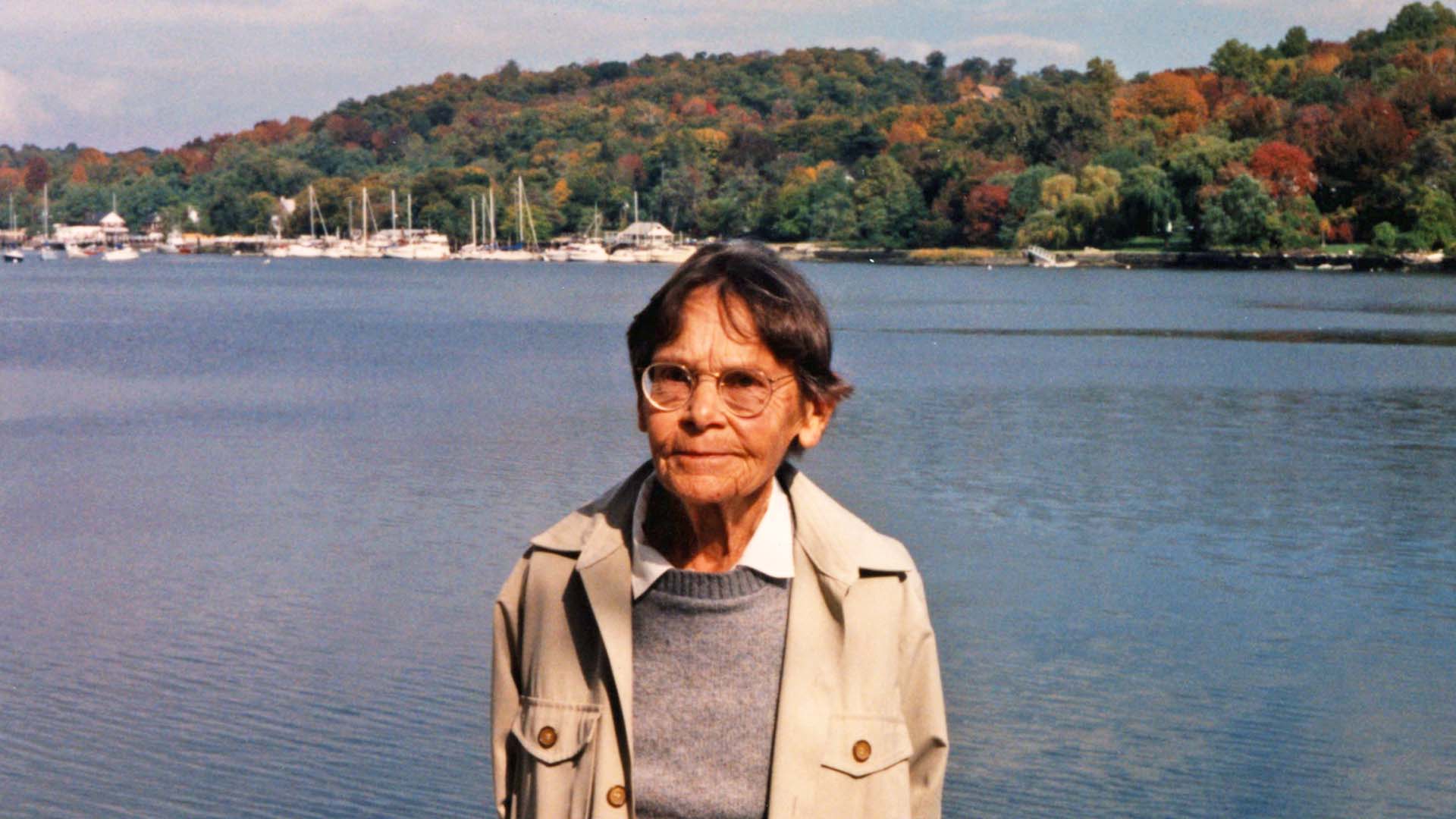

Dr. Gerty Theresa Cori

The very first female Nobel Prize winner in Medicine was Dr. Gerty Theresa Cori, who shared the prize with 3 men, including her husband, in 1947. Her work focused on the conversion of glycogen to glucose, which is an important part of metabolism (how the body transforms food into energy). In fact, this process was named the Cori Cycle, after her and her husband’s work.

Dr. Gerty Cori was born in Prague in 1896 and attended the Medical School of the German University of Prague, earning her Doctorate in Medicine degree in 1920. This was where she met and collaborated with her husband, whom she worked closely with throughout her life. Even as students, they published medical research together, with their first joint paper being a study on human serum.

Throughout her career, even though she had the same education and experience as her husband, she was appointed to lower-level positions and had to work her way up. It wasn’t until the year that she was awarded the Nobel Prize, in 1947, that Washington University promoted her to full professor.

She was the third woman ever to receive the Nobel Prize in science. Recognition for her work was celebrated in 2004 where she and her husband, Dr. Carl Cori, were designated a National Historic Chemical Landmark. She also has two craters named after her, one on the Moon and one on Venus.

Dr. Barbara McClintock

There has only been one woman who has not shared the Nobel Prize in Medicine – Dr. Barbara McClintock. She was awarded in 1983 for her discovery of mobile genetic elements.

Her experimental model was corn, where she looked at how their traits, such as kernel colour, are passed down in future generations of corn. Her steady led to the observations that genetic elements on DNA, called genes, can actually change their position in a chromosome. The jumping around of these genes can activate or deactivate other genes. Although these studies started in corn, they paved the way to discover that these jumping genetic elements, called “transposons”, make up 65% of our genome and have led to a better understanding of how our genome works.

What makes Dr. Barbara McClintock’s journey interesting is that she was approached by her professor, Dr. Claude Hutchison, as a result of her genuine interest and aptitude in genetics early on. His recognition of Dr. McClintock’s interest encouraged him to invite her to take his graduate-level course while she was still an undergraduate student, and the rest is history.

Her exceptional work has earned her many awards as well as Honorary Doctor of Science degrees at 12 different universities including Harvard, Yale, and the University of Cambridge.

Dr. Elizabeth Blackburn and Dr. Carol Greider

Up until 2009, when a woman shared a Nobel prize, it was always with one or more men in the same field. However, Drs. Elizabeth Blackburn and Carol Greider shared their Nobel Prize with their male colleague, Dr. Jack W. Szostak, for their discovery in the field of genomics.

They figured out that chromosomes, which are condensed DNA stored in the nucleus of a cell, are protected by telomeres. They also identified an enzyme responsible for maintaining telomeres, called telomerase. Telomeres are strings of “nonsense” DNA at the end of chromosomes that act as buffers during DNA replication. After each DNA replication stage, which happens whenever a cell divides, chromosomes end up a little shorter. To prevent losing important genetic data, the telomere is crucial to maintain the integrity of DNA information over multiple replications. Telomerase is a protein that lengthens telomeres to increase this buffer zone; however, it is normally inactive in most adult cells. It becomes activated in numerous cancer cells, which allows the cancer cells to undergo many replications without the risk of losing the integrity of their chromosomes.

Dr. Blackburn, with Dr. Szostak, discovered that telomeres have DNA that prevents chromosomes from being broken down. She was Dr. Grieder’s supervisor when they discovered telomerase in 1984. A very interesting part of their experiments was discovering that telomeres in Tetrahymena, a unicellular animal, also worked when transferred in yeast – two organisms that are in completely different phylogenetic kingdoms!

Dr. Tu Youyou

The most recent woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine is Dr. Tu Youyou. Her award-winning research focused on new therapies to fight malaria.

When she was a teenager, Dr. Youyou contracted tuberculosis, which caused her to take a two-year break from her education. This experience inspired her to pursue medical research. She attended Beijing Medical College and learned about the origins of medicinal plants in a phytochemistry course taught by Professor Lin Qishou. Here, Dr. Youyou learned how to extract active ingredients and carry out chemistry studies to figure out how herbal medicines could work in a more scientifically rigorous way than traditional Chinese medicine.

Dr. Youyou trained during a time when national leadership wanted to enhance healthcare by combining Western and traditional Chinese medicine, so doctors were encouraged to combine both in their practices. In Chinese medical literature, cases of malaria have been recorded as early as 1046 B.C.E., with two thousand recipes using various Chinese herbs to treat malaria. Dr. Youyou’s life’s work involved narrowing down these recipes to see if any of the herbs used had scientific merit. In 1972, she completed her first clinical trial using an extract from the herb Qinghao where 21 patients were infected by one/two different malarial strains, and, not only did all the patients recover from their fever, no malaria parasites were detected after the treatment.

These incredible women did extraordinary work that was recognized by their science community. Some of them tackled inequality, while others overcame substantial scientific barriers. They were passionate about their work and had valuable colleagues supporting them.

For Women’s Month, SCWIST would like to encourage you to support your colleagues – male, female, or however they identify – and work together towards building an engaging, scientifically enlightened community. Happy Women’s Month!

Alison Müller is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of British Columbia, where her focus is on digital health communications using the SMS-based virtual tool, WelTel. Have a question for Alison? Reach out on LinkedIn!

Keep in touch

- READ: Where are all of the female winners of Nobel prizes?

- Stay up to date with all the latest SCWIST news and events by connecting with us on LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram and X, or by subscribing to our newsletter.