Researching the global thermometer: Martine Lizotte’s excursion to the Arctic

Back to Posts

CLIMATE CHANGE. It’s a phrase that’s become quite well-known, but teams are still researching to understand the specifics of how it will impact communities.

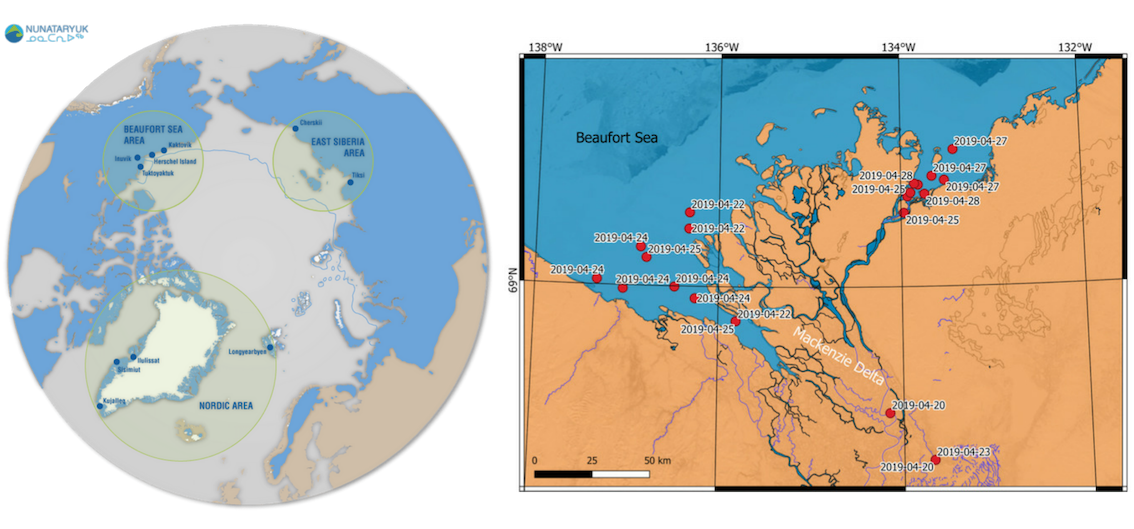

Martine Lizotte from Université Laval is one such researcher. She works as the chief scientist for her team on Expedition 1 for the Nunataryuk Coastal Waters project.

The program focuses on researching how climate change is impacting the Arctic land and water ecosystems in several different locations. Martine’s group is one of the several teams involved in the project, each scheduled to make four expeditions to The North.

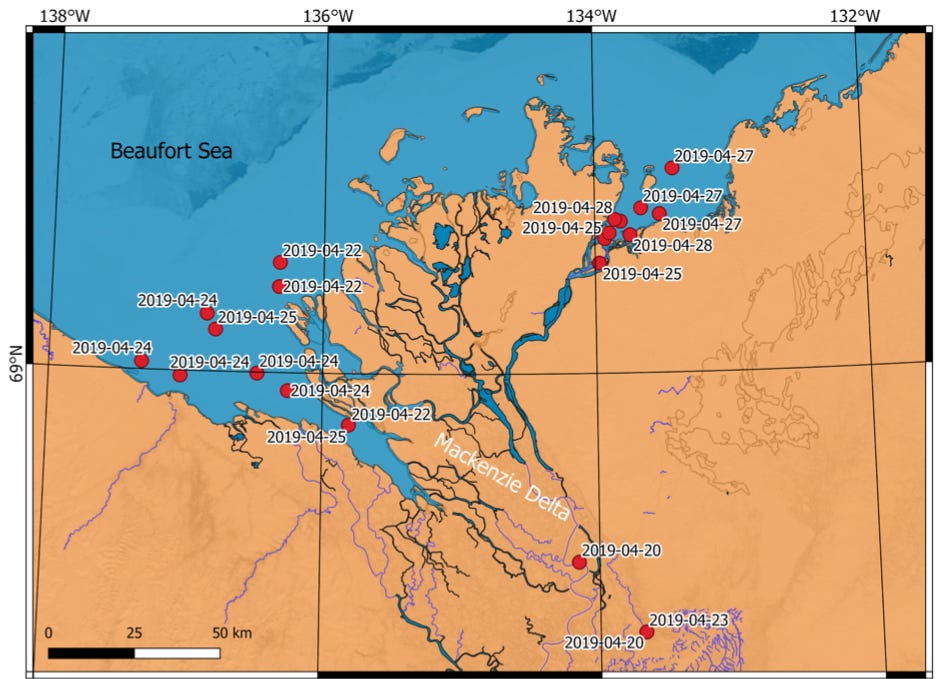

Each expedition is for a similar duration of time where Martine and her team sample water in the Western and Eastern Sectors of the Mackenzie Delta. Their targets are waters in Shallow Bay, Kittigazuit Bay and Kugmallit Bay.

One of the main factors the project is targeting, that can impact both the land and water systems, is the permafrost thawing. Permafrost is any ground that’s been frozen for at least two years without thawing.

The permafrost normally provides support to the coastline, but as it thaws, the shoreline erodes. It can also release contaminants and organic matter into the nearby community’s drinking water and put the residents’ health at risk.

Martine’s team worked with community members to gather water samples from Shallow, Kittigazuit, and Kugmallit Bays. The samples were then taken back to the lab to filter and analyze.

“This would not have been possible without partnerships with local members of the community,” wrote Martine.

“They know the area; their knowledge is the corner stone on which we can build our sampling scheme. They are the ones who provide a safe environment for us to work in by scoping out wildlife, by giving us tips on weather, by helping us find shelter if needed, by providing an entire network of their own which can help us in achieving our goals.”

A coordinated excursion

Martine’s group was split into lab and field team members, with the field team working alongside the community members.

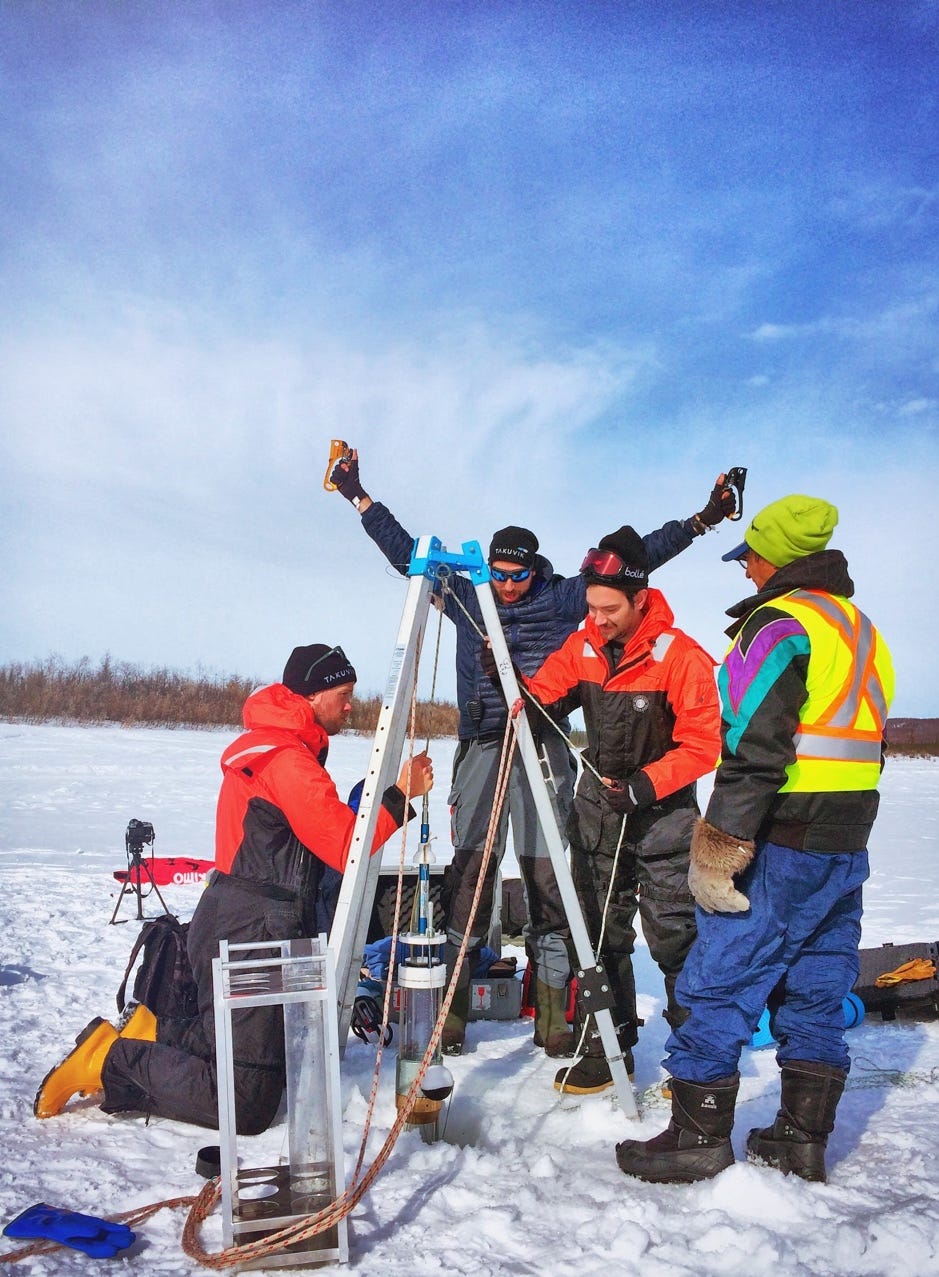

The process started with the field teams as they went out and collected water, sediment and ice samples from their target locations. They would spend at least 12 hours outside enduring the Arctic climate and the strain of operating the machinery used to collect the samples.

The coring samples in particular provided a challenge for team member Bennet Juhls.

“The person doing this (Bennet Juhls) must literally leave his naked hands in freezing water for a certain amount of time to “catch” the core of sediment so it doesn’t fall back into the water as the corer is being pulled out of the sediment,” wrote Martine.

The members also collect sensory samples along with the physical samples, such as water temperature, light penetration and salinity. For this, the team just needed place the sensor in the water.

All of the data and samples the team collected were then taken back to the lab site at the Aurora Research Institute by helicopter. The lab team members would start analyzing everything as it arrived late in the day, meaning they needed to work through the night.

Luckily the sun doesn’t set during summer months in the Arctic, so the graveyard shifts still had “day” light. The unusual sunlight is known as the midnight sun.

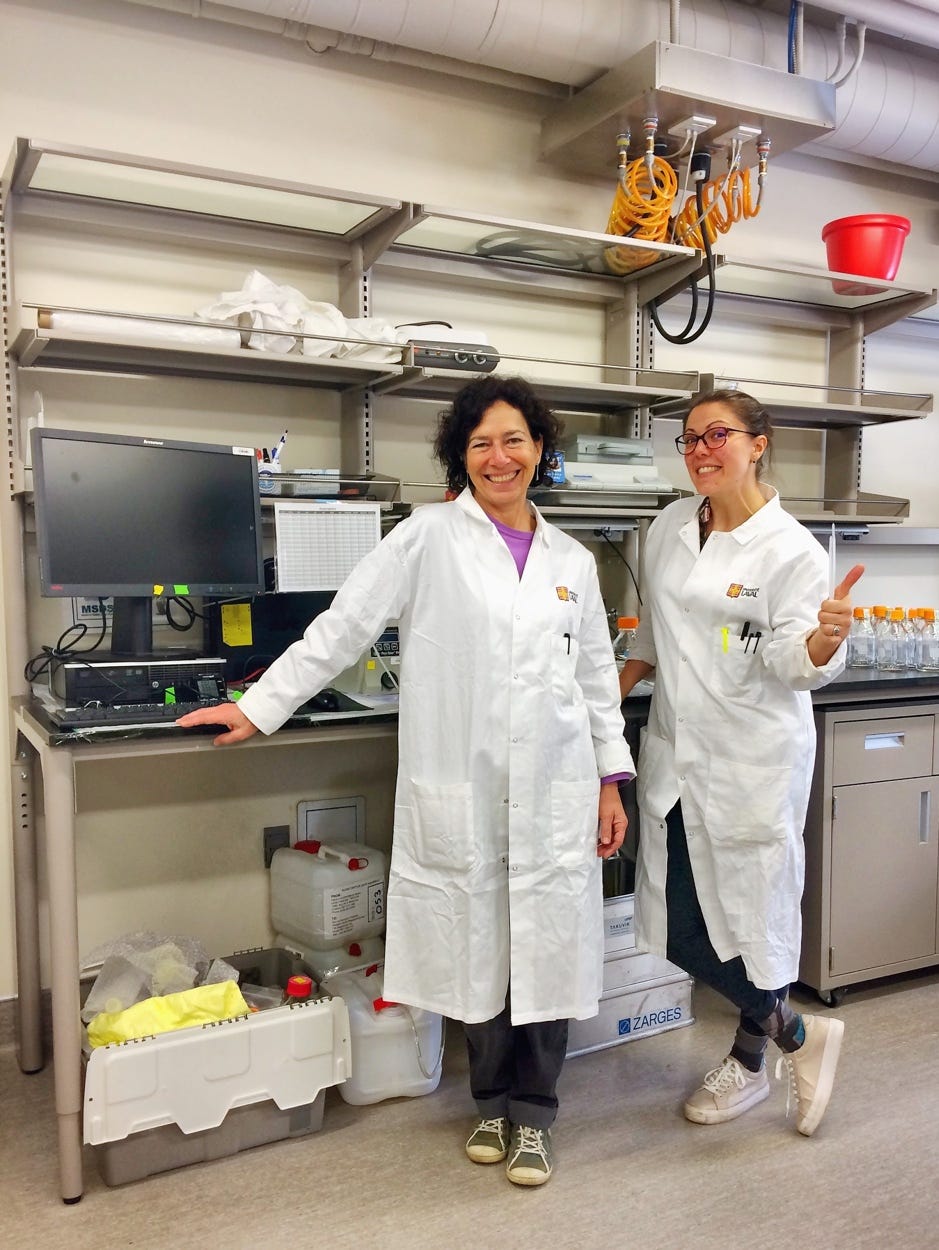

The lab team processed the samples to see how much dissolved matter and particulates were in them.

“When I say process the material: there is a lot of filtration. A LOT. The reason being that since we are interested in quantifying particulate and dissolved matter, we need to separate those: so, we filter,” Martine wrote of the lab team’s work.

“What is left on the filter are particles we can count, can identify, can characterize.”

One of the elements measured on the filter was chlorophyll a, which is a pigment involved in photosynthesis. They also measured what could pass through the filters, such a nutrients in the water.

The ultimate goal at the end of collecting, measuring and filtering is to create a model of what’s really happening in the Arctic at the ground-level. Scientists can then connect the data with satellite images to find any patterns and potentially predict future changes.

Battling the elements

Martine was responsible for the smooth running of the entire expedition as the chief scientist. The unpredictable Arctic climate made her job a challenge, though.

The expeditions involved preparations beforehand to organize the supplies the team would need to complete their goal. But sometimes the initial plan doesn’t always work and in Martine’s words, adaptation is key.

“Plan A is not often the possible plan, so you have to be prepared in advance for Plan B, C, D and often you end up organizing something entirely different from any other plans in your pocket,” wrote Martine.

“Weather is a big factor in modifying plans up North.”

The weather had a big impact on the helicopter flights in particular, which in turn, could impact the day’s data collection.

Helicopter pilots need to be able to distinctly see the land compared to the atmosphere. If the sky is white from snow or clouds, or the ground from snow, it makes it difficult to differentiate between the two.

The team’s flight was grounded because of the weather conditions right from the beginning on the first data collection day. The plan was to fly from Delta to Inuvik, but cloud cover made it unsafe to continue the trek.

The only option was to take shelter until the pilot, Connor Gould, felt that it was safe to fly again.

“Luckily, Miles Dillon, local Inuvik resident and our field assistant, told us that he had a hunting cabin nearby. The team stopped there, to wait it out. A few hours later, they were on their way again,” Martine wrote of the experience.

“It just goes to show how lucky our team was to partner up with Miles.”

Despite the harsh conditions, Martine collected many fond memories on the first expedition and savoured the small victories.

The team was able to spend time with each other and have conversations not just about the expedition, but more generally about life. Martine even recalled a moment of “blasting On the Road Again on the radio with everyone squeezed in the one-tonne pick-up truck”.

Martine found the genuine partnerships and friendships she fostered during the expedition made seemingly impossible tasks become possible.

Her team jokingly referred to how things just seemed to work out in the North as the “magic of the Arctic”.

“I would like to believe that our team went out there with the Golden rule in mind, a simple axiom of empathy,” she wrote.

“Our mindset and our desire to learn from people, as much as to learn from the material we could eventually collect, helped this magic to operate, I think.”

Martine and her team are able to continue fostering the relationships they’ve made in their future expeditions. Their second expedition will finish on July 4 and they’ll be back sampling again for their third trip on July 24. The fourth and final trip will start later in August and finish on September 9.

The trips will all involve sampling and lab analysis, but Martine’s personal goal for the remaining trips is to go into schools and encourage kids through her knowledge and experience.

“It’s a huge goal, but I’d like to inspire. Inspire kids. That’s how I got into science,” wrote Martine. “A teacher opened my eyes to possibilities. It takes only one inspiring teacher…”